Hunting tales: a stag and a hare

3 min read

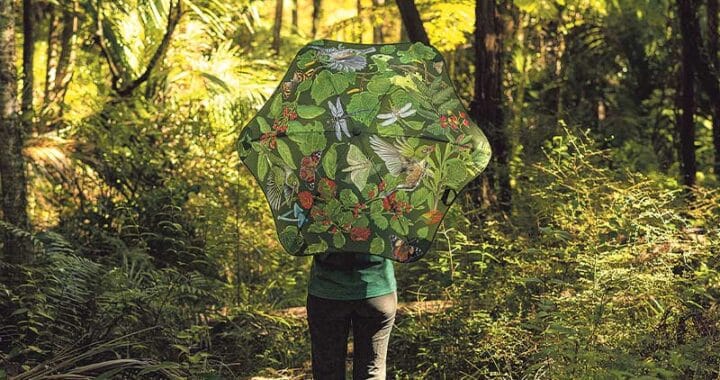

The shot of the hare captured on my Cannon 50 Power Shot. Photo: Tony Orman.

On my last hunt, along with my Tikka .243, I was carrying my Canon 50 Power Shot. The venison stock was slowly depleting in the deep freeze, so I decided that if a suitable deer popped up, I might take it.

I say ‘suitable’ because I have a few rules when it comes to hunting: For one, I never shoot hinds. Nor will I shoot a big stag with trophy or trophy-potential antlers. Why not a hind? Well, to me, there is a real quandary there. For most of the year, a youngster is involved. I cannot abide hunters who shoot a hind in late November, December, January through to February. It will, before Christmas, have a young fawn nestled away. Without its mother, the fawn will die a slow death of starvation.

Perhaps, the only moral window of opportunity is in the roar when you might take a hind for meat. But then it is a 50–50 whether the five-month-old youngster will make it through the winter, particularly in a harsh winter environment like the Tararua. If the youngster does not make it, it will suffer a slow death.

Also, I do not subscribe to the viewpoint that we must shoot hinds to control the population explosion.

If anyone has seen deer numbers overseas (e.g. Scotland, Germany, the US), then it is obvious there is no deer problem here. I believe it is just the Kiwi psyche that has the pest mentality ingrained.

But back to my hunt; I found a suitable deer. There were three young stags–spikers. I selected one and at about 125 metres, shot it. The others milled about and stood unaware of what was going on. I did not want another. One deer is ample for Bridget and me for several months.

The same evening, I found a hare.

There is a classic piece of art titled ‘Young Hare’–a watercolour and bodycolour work from 1502, painted by German artist Albrecht Dürer. It is an artwork that has always fascinated me. Google it and you will see that it is one of the most recognised and beloved works in the history of art. It is often said that Dürer “created an extraordinary realistic representation of quite an ordinary animal.”

Describing it as “quite an ordinary animal” does not do injustice to the hare; it is a magnificent animal. Its mottled fur is beautifully flecked and the animal itself is wonderfully athletic when it stretches out and covers the ground in graceful, loping strides.

So it was that evening that I shot a hare–but, with my camera. The hare was very co-operative. At first, alarmed and then sensing I meant no harm, relaxed and I was able to get a few shots of it.

As for the deer, there is always to the true hunter a pang of regret after downing the animal. Life has been extinguished. The stalk, breathlessly closing the gap to a decent range and easing up, steadying the shot preparatory, and squeezing the trigger is all more important than the shot. If anything, the shot is an anti-climax. But it comes with the satisfaction of filling space in the freezer.

There must be a reason to kill. And you must justify the kill to the utmost by taking as much meat back as possible. Which I did.

Yes, the young stag was welcome in that respect, but at the end of the evening, the shooting of the hare was far more memorable.

As time rolls on, it will be more so.